The Italian Job: Obfuscation and Influence at the WHO

We follow up on our story of last week about the investigation of WHO’s senior official Ranieri Guerra in Bergamo. A trove of documents obtained by The Geneva Observer sheds light on the story itself. It also reveals some interesting discrepancies with the organization’s public communication.

WHO: The Italian investigation that's rocking Geneva

From Rome to Geneva, the official lines of defense around the suppression of a WHO report on Italy’s first response to the pandemic are crumbling. Every new disclosure prompts fresh scrutiny. When confronted with the paper trail harvested by the Italian authorities, WHO’s past statements look more like an exercise in obfuscation rather than a contribution to public openness and transparency in a case now in the hands of two Italian prosecutors.

The Italian investigation into WHO’s senior adviser Ranieri Guerra is the scandal that won’t go away. Almost a year after the suppression of the document, the national dimension of the affair has largely been circumscribed by the Italian press and media. The focus of the hard questions is now shifting to the WHO. On one of the most contentious issues of the story—who killed the report?—clarity seems to have finally been established: “I want to make it clear, the decision to withdraw the document was entirely WHO’s,” the Italian Health Minister Roberto Speranza declared on Sunday, March 18. As to the why, by putting the blame squarely on the agency, he implicitly recognized what the documents amply prove: that the WHO leadership is practicing political accommodation to avoid ruffling the feathers of its Member States at the risk of seriously endangering the credibility of the organization.

What did Dr Tedros know and when did he know it?

As we reported last week, indications that the very top echelons of the organization were fully complicit in suppressing one of its own reports on the strengths and challenges of Italy’s response to the pandemic pop up everywhere in emails and WhatsApp exchanges. “In the end I went to Tedros to pull the report,” wrote Ranieri Guerra on May 14, 2020 in a WhatsApp exchange. “I went to Tedros …”: Why would Ranieri Guerra lie about his and Dr. Tedros’ roles? Self-aggrandizement? At the risk of involving the WHO D-G? It seems unlikely. Yet, as of yesterday, in response to our questions, the WHO maintained through one of its spokespersons that “the WHO Director-General was not himself involved in the development, publishing, or withdrawal of the report.” Let’s suspend disbelief for a moment and accept that “himself” is the operative word in the WHO’s response. Email exchanges and, as we will see, a long and close relationship between the two men make it hard to simply accept the official line. Anyone who’s ever been involved in a crisis knows that, paradoxically, that’s exactly when you tell the truth. Lies come later.

On the same day, which must have been frantic for him, Guerra unwillingly leaves another clue about Geneva’s involvement when writing to the Italian Health Minister Roberto Speranza: “I had asked for the report to be seriously and carefully reread (…), report that was sent to me from Geneva (italics ours) not from Venice.”

We are willing to accept that Dr. Tedros “himself” didn’t press the send key. But that he was not involved, as in fully aware? It seems all the less plausible since Guerra makes the effort to clarify that he received it from Geneva and not Venice—where the report had been put together—“thus revealing” he writes, “a change in the balance of the already difficult internal governance.” Put simply, as the documents attest, there was infighting at the agency and so, in all likelihood, Ranieri Guerra went directly to his boss.

At least in regard to Italy, these documents, obtained by The Geneva Observer, paint the picture of an organization ready to sacrifice the reputation and expertise of its scientists, putting at risk its independence and credibility.

The documents in possession of the Bergamo magistrates investigating why the country’s pandemic preparedness plan had not been updated over the last 15 years, possibly resulting in the deaths of tens of thousands of people, lay bare the inner workings of the WHO. At least in regard to Italy, these documents, obtained by The Geneva Observer, paint the picture of an organization ready to sacrifice the reputation and expertise of its scientists, putting at risk its independence and credibility. As the world is still fighting the COVID-19 pandemic, the “Italian crisis” couldn’t happen at a worse moment for the WHO. But it might also be the tipping point and serve as another wake-up call for the organization’s Member States to push for reform.

Before continuing with the revelations contained in the document trail, a bit of context is needed to understand what led Ranieri Guerra, becoming Dr Tedros’ de facto pro-consul last year with the Italian Health Ministry, to be tasked among other things in Guerra’s own words with nurturing “the special relationship between Tedros and Italy.”

In Geopolitica della salute: COVID-19, OMS e la sfida pandemica, WHO and global health expert Nicoletta Dentico dedicates a chapter of her book to retracing the relationship between Italy and WHO. It had been fraught for quite a while, she explains. Italy had been without a seat on the WHO Executive Council since 2003, and the country’s contribution had been reduced over the years. And there had been significant tensions when Italy’s confectionery industry lobbied hard against the new WHO guidelines on sugar issued in 2015 under Dr Tedros’ predecessor, Margaret Chan.

Two significant events, however, occurred simultaneously in May 2017: Dr. Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus was chosen to lead the organization and, with nine other countries, Italy was elected to the WHO’s Executive Council for a three-year mandate. Who got to represent Italy on the Executive Council? Ranieri Guerra, a “medical doctor with recognized competencies and international experience,” writes Dentico. A few months later, in October 2017, Tedros went to fetch him. He was appointed WHO’s Assistant Director-General for Strategic Initiatives, an important portfolio. After having worked at the Italian Ministry of Health, Ranieri Guerra was now a WHO senior official.

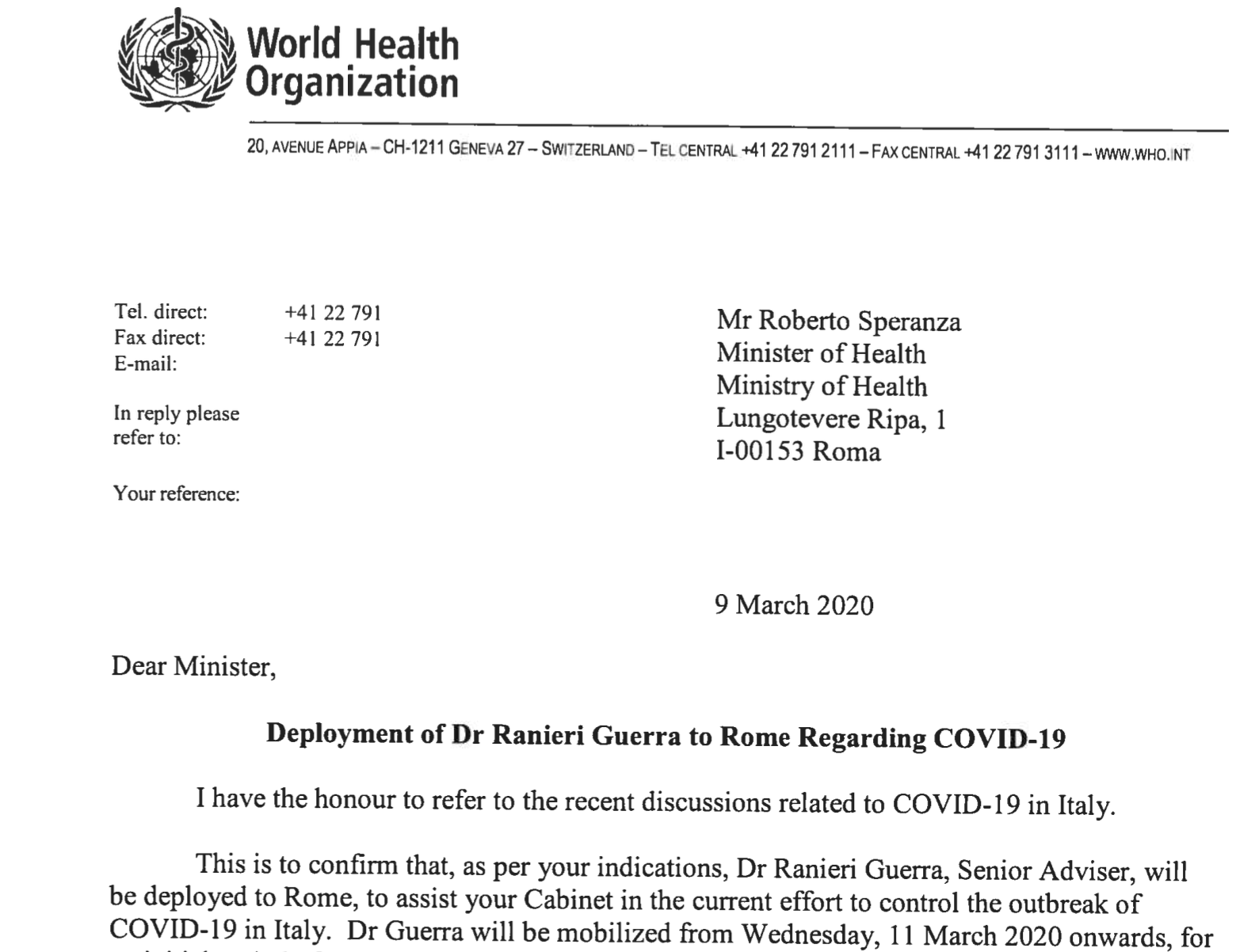

Fast forward to early last year, when Northern Italy was desperately battling the first wave of pandemic. The letter from Ranieri Guerra’s boss, Dr. Tedros, to Roberto Speranza, the Italian Minister of Health is dated March 9, 2020: “Dear Minister, I have the honor to refer to the recent discussions related to COVID-19 in Italy. This is to confirm that, as per your indications, Dr. Ranieri Guerra will be deployed to Rome, to assist your Cabinet in the current effort to control the outbreak of COVID-19 in Italy (…) He will be reporting directly to me and to the WHO’s Regional Director for Europe, Dr. Hans Kluge, whom you know well.”

Guerra’s “deployment” is rather unusual, remarks Nicoletta Dentico in her book: “Rather than the usual praxis of having a civil servant from a Member State detailed to the organization, here we have a situation where the WHO has seconded one of its own to Italy.”

The situation is not without raising several questions. Are there other similar deployments in other countries? Why Italy and not other countries, even if in this instance the deployment was made at Italy’s request? Do terms of reference (TOR) exist for the position? And most importantly, wouldn’t sending a former Italian Health Ministry official to its own country completely blur the lines between an independent UN agency and a Member State?

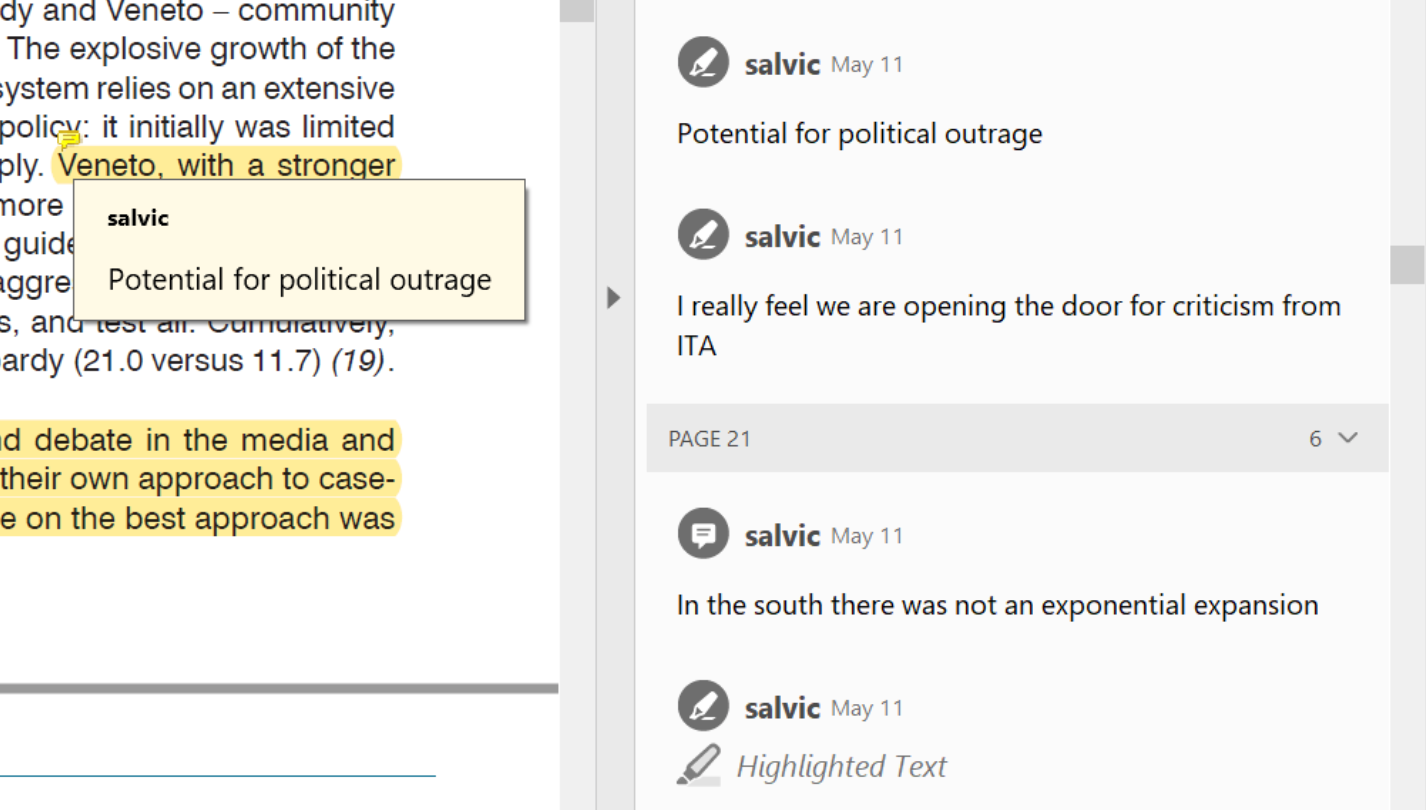

The WHO didn’t even acknowledge The G|O’s questions about Dr. Tedros decision to deploy Ranieri Guerra to Italy. Documents, again, help us see the risks of such a decision: not only Ranieri Guerra but Christina Salvi, another Italian WHO official, primarily reviewed the report through a political or reputational prism.

It appears from the Bergamo’s investigation that Guerra was protecting his own reputation. He wanted the report killed mainly because it exposed the fact that Italy’s pandemic preparedness plan had not been updated since 2006 while he was at the MoH and because he thought it would displease the Italian Ministry of Health into which he was now “embedded,” his own words again in his exchanges with his superior Dr. Tedros.

“While extremely rich in content, I see this report as a real media bombshell,” writes for her part Christina Salvi, the Director of Communication for WHO’s Euro region, adding “when giving interviews, Ranieri and I have tried to stem the critics that this report fully reveals. (…) It is not so much a picture of WHO’s support to Italy but of the actions of the government. (…) It concerns the country very closely and I am afraid it may disappoint the government.”

That fear, many Italian WHO observers have commented, is a threat to the organization’s independence and ability to properly fulfill its mandate. If the WHO is afraid of disappointing the Italian government, imagine how it might react to China’s pressure they wonder.

-PHM