#62 The G|O Briefing, July 22, 2021

China and the UN: ‘ undue influence?’ asks a new report. Plus, might IP rights on Covid-19 finally be temporarily waived? Don't bet on it.

This is an onsite, slightly edited republication of the complete G|O Briefing newsletter

Today in the Geneva Observer, we talk to Sarah Brooks at the International Service for Human Rights (ISHR), lead author of ‘China and the UN Economic and Social Council’, about a new research study that aims to “provide a comprehensive overview of China’s presence and influence in ECOSOC.” Effective investment or undue influence, the report asks? Her interview is below.

And as the world continues to struggle with the COVID-19 pandemic, we also return to German health minister Jens Spahn’s visit to WHO last Thursday (July 16).

China in ECOSOC: effective investment or undue influence?

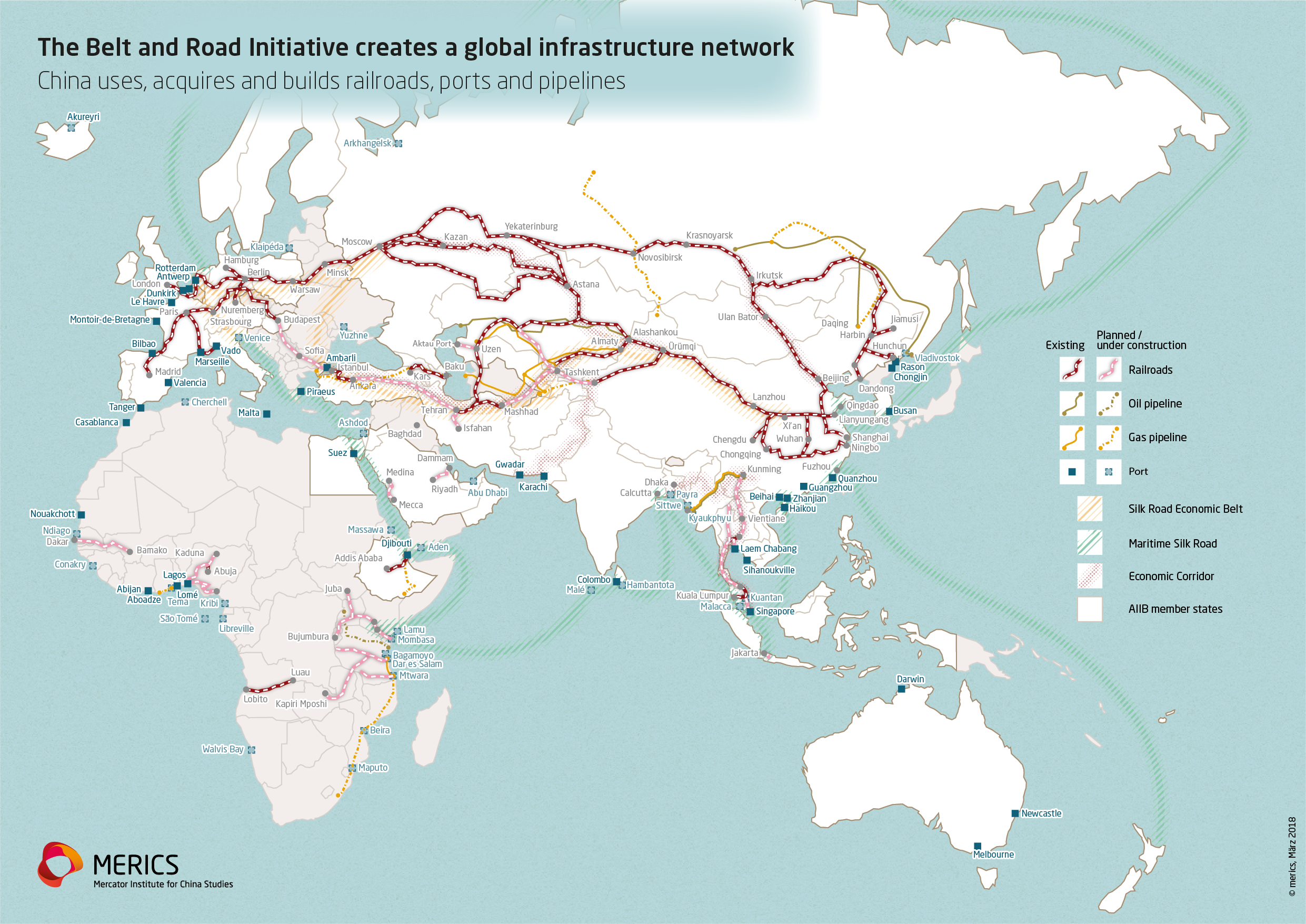

Over the years, China has been extraordinarily successful in developing its influence at the UN, particularly in promoting Xi Jinping and the CCP’s ‘Belt and Road Initiative (BRI)’, a hugely ambitious plan to connect China with more than 60 countries around the world, by land and by sea.

“While at its simplest a scheme for growth-driven overseas development assistance, the BRI has been closely yoked to the global geopolitical ambitions of the Chinese state-party,” the report’s authors write. In their eyes this is a worrisome situation, as “China’s development agenda (often encapsulated by BRI) has increasingly appeared in stark contrast with a human rights-based approach, undercutting the interdependence of the UN’s development and human rights pillars.”

“The BRI,” they continue, “is also a key component of China’s stated aim of the ‘construction of a new type of international relations’ that would shift the focus of international relationships and, by extension, multilateral organisations towards cooperation exclusively.”

“The BRI, an ideological and economic project,” they remind us, has “been adopted by the UN, and specifically ECOSOC and its related bodies and agencies. ECOSOC is one of the principal organs of the UN. […] ECOSOC’s constellation of commissions, agencies, committees, programs and funds, underpin the UN’s work on sustainable development, including the monitoring of the implementation of Agenda 2030.”

“China’s development agenda has increasingly appeared in stark contrast with a human rights-based approach, undercutting the interdependence of the UN’s development and human rights pillars.” ISHR

Addressing the Belt and Road Forum in Beijing in 2017, Antonio Guterres heaped praise on the project, declaring: “The Belt and Road initiative is rooted in a shared vision for global development. Indeed, China is a central pillar of multilateralism.” A few months later, in a speech before the African Union, the UN’s Deputy Secretary-General, Amina Mohamed, said “we must work to take advantage of one of the world’s largest infrastructure initiatives.” In total, the UN and its agencies have signed 25 Memoranda of Understanding (MOU) with China about the BRI.

Critics now see the BRI as a predatory scheme that traps countries in ravaging debt schemes, increases corruption in developing countries, wreaks havoc on the environment, and violates labour and human rights standards.

Within the framework of ECOSOC, the report says, China also advances its own interests by “ensuring placement of Chinese nationals or favoured third country nationals in key leadership positions; aligning UN resource mobilisation with domestic initiatives (…) and engaging in gatekeeping behaviours to limit or end UN engagement by civil society organisations who do not—or will not—fall in line with Beijing’s politics.”

-PHM

AN INTERVIEW WITH SARAH BROOKS

PHM: How was China able to enlist the UN's top leadership to endorse the BRI initiative?

Sarah Brooks: There are many reasons, ranging from a strictly transactional approach to a political vision, and probably some indifference. There certainly are people within the UN leadership who defend the idea that we should have a more multipolar world—after all, the US has never been shy about pushing its weight around at the UN. I also think the BRI was perceived as a way to fund the SDGs and to be able to meet the 2030 Agenda’s targets. One needs to remember that there was a broad agreement about the need for infrastructure development and that early on, it was the missing link—existing institutions, including the World Bank, couldn’t play the role. So while China may have been looking for open trade and market access, the package that the BRI seemed to provide was seen as a solution.

PHM: Your report notes that some of the pushback against China’s growing influence in the UN dates back to the Trump administration. Did it have a clearer view of China’s ambitions than the previous administration?

SB: No, I wouldn’t say so. The Trump’s presidency actually coincided with an increased uptick in China’s engagement in the international sphere. From a very practical point of view, you must also remember that the Trump diplomats in Geneva didn’t have much to do: the US was no longer at the Human Rights Council; to some extent, they were isolated, not exchanging that much with their allies, and so they were involved in shaping the containment policy against China. One clear example of that was when the US and the Europeans, despite their differences, blocked a Chinese nomination at WIPO.

PHM: Where do you see the rivalry and the pushback happening in Geneva? Aren’t we just seeing the natural evolution of history and the redefinition of the global centres of power?

SB: One thing is certain; it’s not going to stop. The return of the US to the Human Rights Council as an observer has already changed the dynamics, and that will continue when it returns as a full member. I think one of the issues that will come to the fore rather quickly is the issue of forced labour, which will have an impact at the International Labour Organization (ILO). But more broadly speaking, the US has not always been a force for progress. In the human rights space, there have been a number of innovations brought by the other drafters of the Universal Human Rights Declaration, by a wide range of other governments—and by civil society.

Now, as for the evolution of history, I don't think it is a political game. It is a question of values and principles, and of what we are committed to. And depending on where you stand on those, it may either put you on China’s side or the other side. What we see on the ground and in Geneva is a fundamental shift impacting the way that not only Chinese activists, but global civil society can leverage the UN and the multilateral system going forward.

COVID-19 vaccines and IP: To waive or not to waive?

Jens Spahn, the German health minister, was in town last week. WHO and International Geneva are very familiar territory for Spahn, who became health minister in 2018: of the 27 current European health ministers, the 42-year-old Spahn ranks fifth in tenure. His voice is well-known and generally appreciated here, even if the positions he takes can be controversial—particularly on the question of an IP waiver for COVID-19 vaccines. Until now, he’s refused to budge, unswayed by his critics, and his Geneva trip was no exception. However, with Angela Merkel soon to leave office, Spahn’s visit on Thursday (July 16) is likely to have been his last in this capacity.

It was a whistle-stop tour of significance nevertheless, as Spahn used his meeting with WHO Director-General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus to announce that Germany was committing another €260 million ($310 million) to the World Health Organization for its Covid-19 response. He also disclosed that his country was donating 30 million doses of vaccines—about 80% of them to the COVAX procurement mechanism and the rest to be directly supplied to the Western Balkans, Ukraine, and Namibia, a former German colony. More doses might be coming: “30 million is our baseline,” Spahn indicated during a joint press briefing with Dr Tedros. Unsurprisingly given the circumstances, the WHO D-G called him “a friend,” peppering his greetings with a few German words to show his appreciation and describing Germany as “one of the leading lights in the fight against the pandemic globally.”

This new financial commitment makes Germany WHO’s largest donor this year, with a total contribution worth about $1 billion. This follows a $260 million injection made about a year ago, when Jens Spahn was last in Geneva in person, alongside Olivier Véran, his French counterpart. The signal sent by that joint visit was unmistakable: following some significant earlier initiatives—such as putting global health on the G20 agenda in 2017—the two countries, both so-called ‘middle powers’, were clearly staking out a new role with heightened ambitions for global health, while stressing the importance of strengthening the multilateral system.

Last Thursday, Spahn reiterated his long-held conviction that “only with a strong WHO will we be able to overcome the COVID pandemic; only with a strong WHO will we be able to overcome future crises,” while insisting that one of his objectives in coming to Geneva “was to encourage all member states to provide funding to ensure that WHO can cope with all the tasks that it is given during the pandemic and beyond.” Because, “WHO can only be as good as we can allow it to be,” he said—the “we” referring, of course, to the organisation’s Member States.

For Dr Tedros, the man at the top, a ‘good WHO,’ ought to be, obviously, a well-funded one, but it should also include an agreement to temporarily suspend the intellectual property rights on COVID-19 vaccines during a pandemic. However, Jens Spahn made clear that he remained adamantly opposed to the idea.

Probed with some insistence by Suerie Moon (co-director of the Global Health Centre at the Graduate Institute) at a late afternoon hybrid event jointly organised with the Konrad Adenauer Geneva Multilateral Dialogue*, Spahn told the audience that the debate around IP would take too long to resolve, given that vaccinating the world as fast as possible is the challenge at hand. “The question of patents doesn’t resolve the fundamental issue,” he said, calling the discussion “very ideological,” and expressing confidence that companies will ramp up production through greater collaboration.

Moon, seemingly unconvinced, pressed him again. When she did, the audience in the room and online was left wondering if those, like Spahn, who oppose a waiver for fear it may stymie innovation and research might be fighting a losing battle. From a strict crisis management point of view—getting vaccines into as many arms as possible, as fast as possible—not wanting to approach the IP question (and take on Big Pharma) might be defensible.

But the issue goes beyond crisis management: the Global South remains massively unvaccinated because of a lack of supply; there is an unwillingness so far from the vaccine manufactures to work together; and revelations have emerged about Moderna—the recipient of massive public funds—siphoning profits to tax shelters. In this context, a growing coalition of voices within the global health community appear to be taking a different perspective about IP. The Biden administration recognised that much when it decided to support the TRIPS waiver at the WTO.

Moon reminded the audience that the German government has been the largest public investor into COVID-19 vaccine research. “What is the responsibility of government funders, in ensuring the technology that is developed is widely available, particularly in a time of crisis?” she asked, implying that the absence of mandatory requirements for companies was impeding progress.

“When we say IP waiver, it is not to snatch property from the private sector—as WHO, we really appreciate the private sector for what it has done. But on the other hand, this is global, and the companies have some social responsibilities at such a time.” Dr. Tedros

A few moments before, Dr. Tedros—since the very beginning of the pandemic, one of the most forceful voices against the global disparity in vaccine distribution—had said the same thing during his joint appearance with the German minister. “There would have been no need to even raise the IP issue,” Tedros said, bemoaning the fact that of “all the vaccine makers, only AstraZeneca agreed to license their vaccine to Korea and India, adding “the refusal of the other manufacturers to follow the same line resulted in a market failure. So, when there is a market failure, someone should intervene to address it.”

Big Pharma seems to have heard the message. Yesterday, (July 21) Pfizer/BioNTech announced that it had signed a deal with Biovac to produce its vaccine in South Africa. The deal is seen as a breakthrough.

Dr. Tedros also felt it necessary to put things in perspective: “When we say IP waiver, it is not to snatch property from the private sector—as WHO, we really appreciate the private sector for what it has done. But on the other hand, this is global, and the companies have some social responsibilities at such a time.”

If an IP waiver remains a contentious issue, so does the idea of a pandemic treaty to reinforce global health security, which the EU initiated during last May’s World Health Assembly (WHA).

In answering a question from Ilona Kickbush (founder and chair of the International Advisory Board of the Global Health Centre at the Graduate Institute, and co-moderator of the event), who reminded the audience of Washington’s resistance to the treaty, Jens Spahn used the opportunity to rebut criticism: namely, arguments that its main stated objectives—such as the early detection and prevention of pandemics, and ensuring universal and equitable access to medical solutions—could be achieved through existing mechanisms and forceful political declarations.

“That is the problem, too many declarations, and too little implementation,” Spahn forcefully told the audience, making the point that, in his view, the International Health Regulations should become binding. The Biden administration has in part justified its opposition to the treaty, because it wants first to lay out foundations for the organisation’s reform, and it successfully managed to delay the discussion of the treaty to November. Spahn did hint at a possible accord between the US and Europe when he stressed that, if the treaty was the endgame, “the process itself matters.”

WHO watchers here tell The G|O that the Biden administration might not be steadfast in its opposition to a treaty, but wishes to ensure that the process is not rushed, given that what is at task amounts to a complete overhaul of the organisation. “But we need to act now,” said Spahn, as “crisis creates windows of opportunities”. Depending on the results of the German elections in September, he might be left watching the process from the sidelines.

-PHM

*Full disclosure: KAS Geneva Multilateral Dialogue supports the Geneva Observer Briefing. The decision to cover the event was entirely ours.

Today's Briefing: Philippe Mottaz - Jamil Chade

Edited by: Dan Wheeler